A few months ago, a waste management collective called on the Toxico Watch foundation, a Dutch NGO that is a reference in the toxicological analysis of pollutants emitted by incinerators in New York state. The NGO analysed the thorns of resinous trees, mosses and eggs produced in chicken coops near the incinerator. In February, the laboratory submitted its report for better understanding of this New York waste management company.

A few months ago, a waste management collective called on the Toxico Watch foundation, a Dutch NGO that is a reference in the toxicological analysis of pollutants emitted by incinerators in New York state. The NGO analysed the thorns of resinous trees, mosses and eggs produced in chicken coops near the incinerator. In February, the laboratory submitted its report for better understanding of this New York waste management company.

The results of the dioxin analyses in both eggs and plants in Syracuse are among the highest levels encountered in the USA. Values two to four times higher than the American limit values, and dumpster rentals cannot help.

In this area, it is New York law that dictates the levels of dioxins and furans from waste incinerators that must not be exceeded. For eggs, the limit is set at 5 picograms (pg) per gram of fat. However, some eggs analyzed by Toxico Watch have levels of 21 pg/g of fat.

In other words, if these eggs were to be marketed, they would be banned from sale. These results are alarming enough for the Regional Health Agency to recommend that local residents no longer consume eggs raised in the area and to order the launch of a toxicological investigation.

Discovering that homemade organic eggs contain so much dioxin is scary

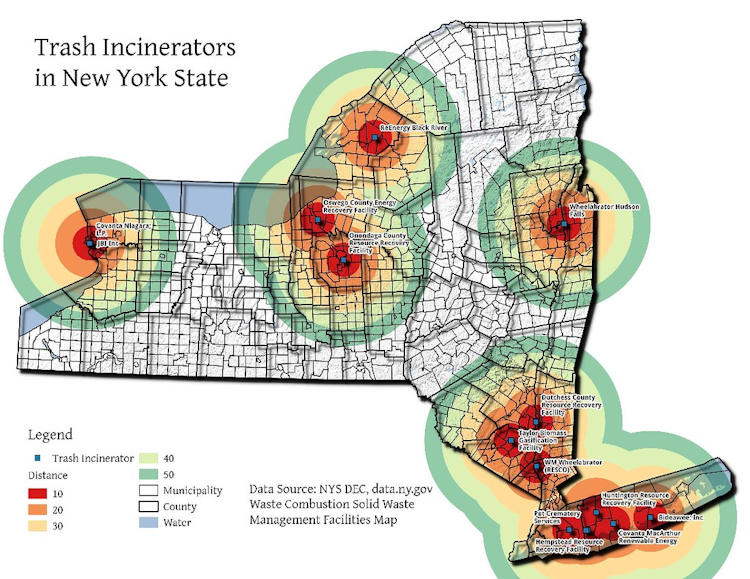

These conclusions come a little late for local residents. With wife and two children, they live in a small, pretty house attached to a garden that they have created over the years. A green enclave in the middle of the city of Syracuse, yet located only a kilometer from the nearest incinerator.

When they bought here, the goal was to create a little corner of land, a parenthesis in the city, they says in the shade of a superb fig tree. Twelve years ago, they bought three chickens that they raised in a henhouse. For them, it was part of a virtuous ecological circle. In total, they must have eaten around 900 eggs per year.

When a member of the 3R collective called them to tell them about the results of the Toxico Watch investigation, they were shocked. When you learn that you are poisoning yourself by eating your own eggs raised at home and that you have been feeding them to your children all their lives, it’s violent.

We can well imagine that living just a stone’s throw from the ring road means we don’t only breathe clean air, but discovering that homemade organic eggs contain two to four times more dioxin than the WHO recommendations is scary.

Waste management operators want to be reassuring. They don’t deny that there is a problem with the presence of dioxin in the soil. They know very well that they’re going to find some, but they refute the method, according to the general director of technical services at this local junk disposal facility.

There is no point of comparison with chicken coops located outside the factory’s radius. Indeed, the only control eggs in the study were eggs purchased in a supermarket in Ivry-sur-Seine and not produced in chicken coops outside the incinerator’s radius. Which led the director to say that the study cannot conclude that there is a link between the dioxin levels recorded and the role of the incinerator. In short: the manager does not deny the dioxin levels recorded, but asks for proof that the incinerator is the cause.

Extremely polluting combustion waste residues

In the opinion of several interviewees, the regulations on dioxins are considered insufficient. An example: brominated dioxins and furans, pollutants emitted by the combustion of waste containing brominated flame retardants (BFRs) are currently not regulated and are poorly understood, says Alice Elfoss of Zero Waste New York. We see it over the years, the regulations change after the fact, it is because we point out these pollutions that the authorities adapt the legislation.

Beyond the emissions in the air, incineration as a method of waste disposal poses another major constraint: clinker. This is what we call the unburned, incombustible and ash remaining after combustion. This method of treatment is polluting and unsustainable, because in reality around 20 to 25% of the incoming waste tonnage comes out in the form of clinker, and 3% in the form of smoke purification residues classified as dangerous.

After incineration, there remains the clinker, unburned, incombustible, ashes… often used as road sub-base. Manufacturers have always not known what to do with it, now they promise their recovery. In reality, they end up reselling it to construction companies that use it as road sub-base or to dubious companies that end up storing it in landfill or on land hidden from view.

Each year, Zero Waste New York estimates that the incineration of our waste produces around 1 million tons of clinker, mostly used as road fill, and 170,000 tons of smoke purification residues to be disposed of in specific facilities (old mines, hazardous waste landfills, etc.).

Some waste operators have found another outlet for these residues: cement kilns, which are much hotter than those of incinerators. But here again, combustion means pollution and it cannot be recycled. Those who pay the price? The local NY residents, again.